Am I the Asshole for Cutting Off My Best Friend’s Wife Over Her Disrespect?

You’ve been navigating a deep, long‑standing friendship with your best friend—someone you clearly care about—but since he got married, his wife’s attitude toward you has eroded the relationship’s foundation. From the wedding day—where you couldn’t attend, through no fault of your own—you sent a thoughtful gift, yet she perceived that absence as a slight rather than understanding your circumstances. That essential misunderstanding was only beginning.

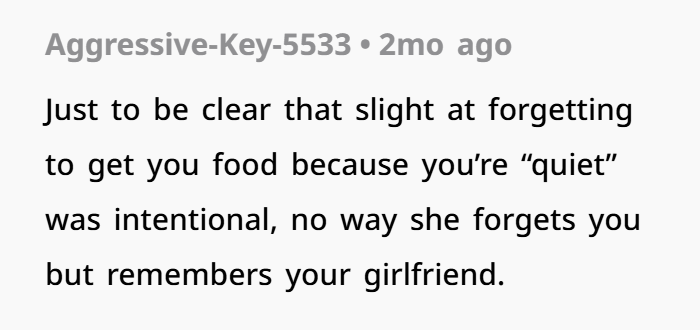

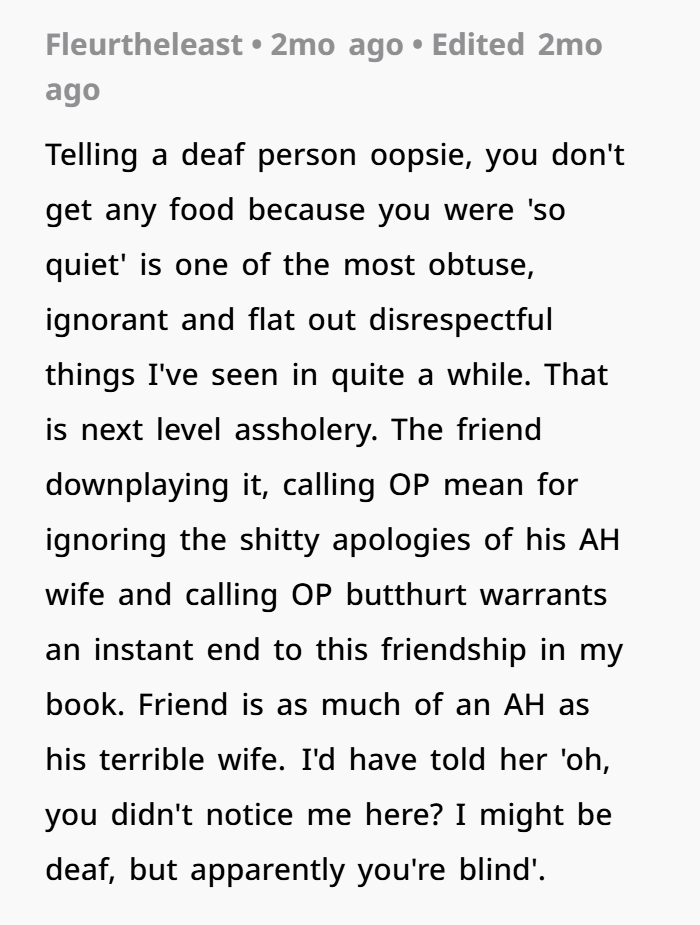

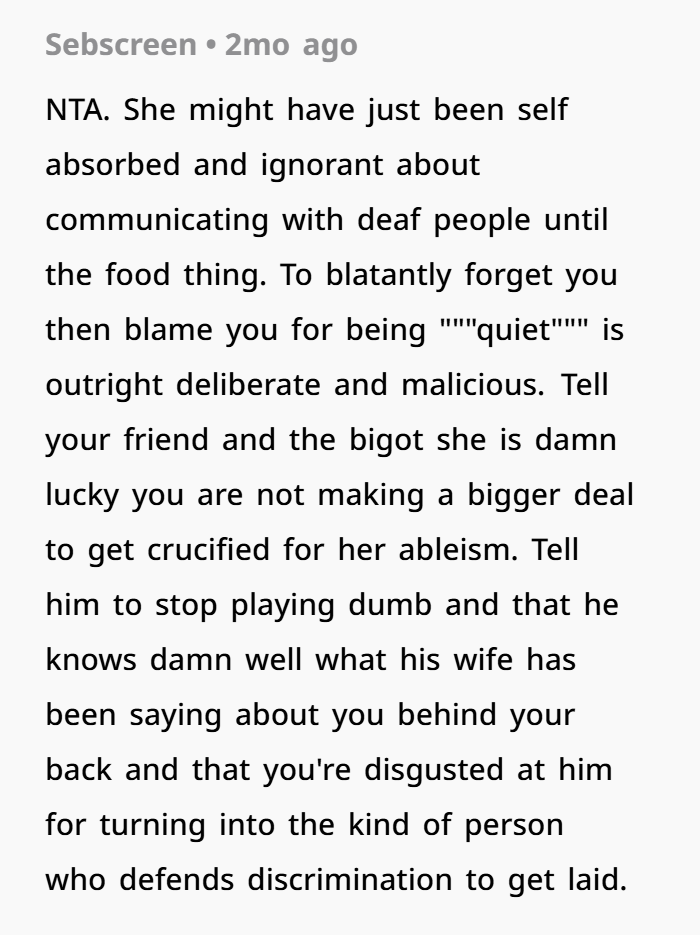

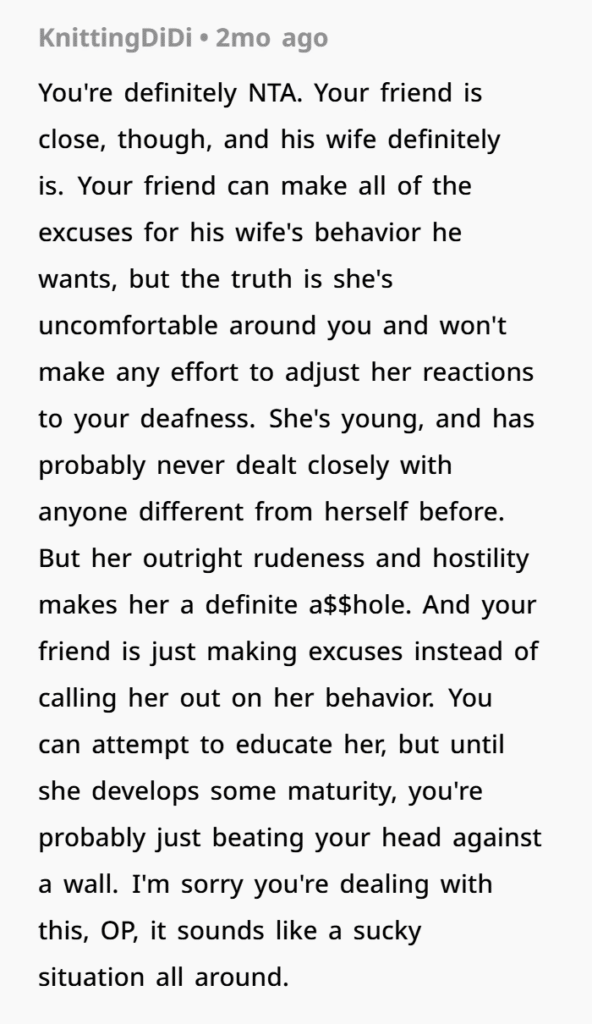

Once you returned and they finally met you in person, she continued to treat you as if your deafness rendered you invisible or inconsequential. Yelling unnecessarily, failing to make eye contact, relying on your girlfriend to interpret—each act compounded the message that she didn’t respect your autonomy or humanity. At game night, being the only one not included in dinner due to being “so quiet” was a sharp, painful culmination. You’ve tried to communicate, but her half‑hearted apologies and your friend’s dismissal (“don’t get so butthurt”) demonstrate that your feelings were minimized rather than validated.

Many of us need to improve our communication, especially with people different from us

But especially this woman, who managed to embarrass her husband’s deaf friend so much that he considered cutting ties with them

1. Invisible Disabilities and Social Exclusion

Research on invisible disabilities—such as being deaf or hard of hearing—emphasizes how social exclusion is intensified when others fail to recognize or accommodate them. A 2017 study in the Journal of Disability Studies pointed out that individuals with invisible disabilities report deeper feelings of isolation when peers assume they’re not present unless attention is overtly drawn to them. In your case, being “quiet” became synonymous with being overlooked—even by people who ought to know and respect you. That dismissal is precisely what such research labels “social erasure,” and its emotional toll is well‑documented.

2. Communication Equity and Respect

At the heart of effective social interaction lies equitable communication. The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and similar laws emphasize reasonable accommodations—like ensuring clear communication strategies—not as optional niceties but as rights. While social acquaintances might not always be legally burdened, the spirit of these guidelines speaks to norms of respect and fairness. By ignoring your presence and making no effort to address her remarks about your deafness, she undermined both your human dignity and the basic principles of mutual respect.

3. Psychological Impact of ‘Othering’

Psychologists studying interpersonal dynamics note that when someone is constantly “othered” or excluded—even subtly—it prompts a cascading effect: reduced self‑esteem, hypervigilance in social settings, and increased emotional withdrawal. You wrote, “I never been embarrassed to be deaf until that moment.” That statement is key—your deafness had never been a source of shame for you until her behavior forcibly framed it as one. That’s a profound shift, and it highlights the emotional harm that ignorant remarks can inflict.

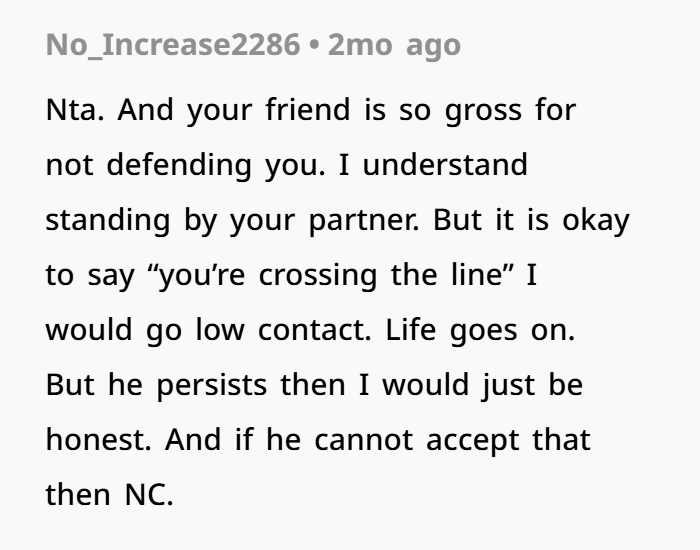

4. Bystander Role and Shared Responsibility

Your girlfriend took on the emotional burden of trying to intervene—explaining the importance of speaking normally, sharing her meal with you after dinner was omitted, and defending your communication needs. Yet that also placed an unfair burden on her: she shouldn’t have to act as your protector or translator. It illustrates how communities of support can fall on individuals when the broader group fails to acknowledge the marginalized perspective. The broader literature on allyship suggests that responsibility for inclusion should be collective—not deferred to individuals who are already disadvantaged.

5. Conflict Resolution and Repair

Your friend’s reaction—the “don’t get so butthurt” line—reflects a common defensive minimization. Often, people who commit micro‑aggressions (especially when they’re unintentional) respond with “it wasn’t meant that way” or “why are you so sensitive?” Unfortunately, that response deflects rather than engages. Forgiveness and moving forward can be part of reconciliation—but only when there’s acknowledgment, genuine remorse, and clear effort to change the pattern of behavior.

A comparable case study comes from workplace dynamics: researchers have shown that apology alone isn’t enough—what matters is restorative action. Translation: if the wife truly wants healing, she needs to not just say “I’m sorry,” but also say, “I will do X, Y, Z differently,” such as ensuring you’re acknowledged, communicating directly, and receiving training or education on deaf awareness.

6. Friendship Boundaries and Self‑Respect

At 24, you’re at a stage where your self‑worth and boundaries should be honored within any friendship. Long‑standing or not, a friendship that corrodes your sense of comfort, dignity, or belonging isn’t worth preserving unless it can explicitly shift. It might not be about “throwing away” the friendship—but about reassessing what you’re willing to accept. Healthy boundaries are not a lack of love—they’re a mechanism to ensure relationships remain enriching rather than harmful.

7. Social Identity and Community

The deaf and hard‑of‑hearing community is rich, diverse, and resilient. Many have faced similar erasures and found empowerment through advocacy, education, and community support. Your girlfriend’s support is wonderful—but you’re part of a larger social identity group whose rights and recognition matter. Their collective narratives reinforce that you deserve more—not only better treatment, but proactive respect.

8. Navigating the Path Forward

Here’s a constructive breakdown of possible paths you might consider, informed by relational conflict research:

- Direct conversation with your friend: Express how deeply his wife’s behavior hurt—not to provoke guilt, but to clarify that the silence, the omission, the “quiet” comment—these are symptomatic of deeper disregard.

- Request a joint conversation (with mediator): If possible, ask both he and his wife to attend a facilitated talk—perhaps with your girlfriend as ally or another neutral friend. This could help set new norms: remind them of your needs, and what changes you’d like to see.

- Set clear expectations: For instance, from now on, ensure that all group activities include explicit planning: “Let’s order for everyone,” “Let’s check in with him directly,” or even simple seating gestures that include you.

- Evaluate responses over time: If they persist in ignoring or making excuses, you might gradually reduce the friendship while preserving your dignity and mental well‑being.

Final Thought

You are not oversensitive. You are sensitive—to the basic respect every human deserves. They have repeatedly devalued your presence, your communication needs, and your humanity. That was not your fault. Ignoring them was a natural self‑protective response in the moment. True reconciliation would require more than apology—it would require structural, behavioral change, and accountability. Whether or not you choose forgiveness sooner or later, it should happen on your terms, when you’re assured of genuine respect.

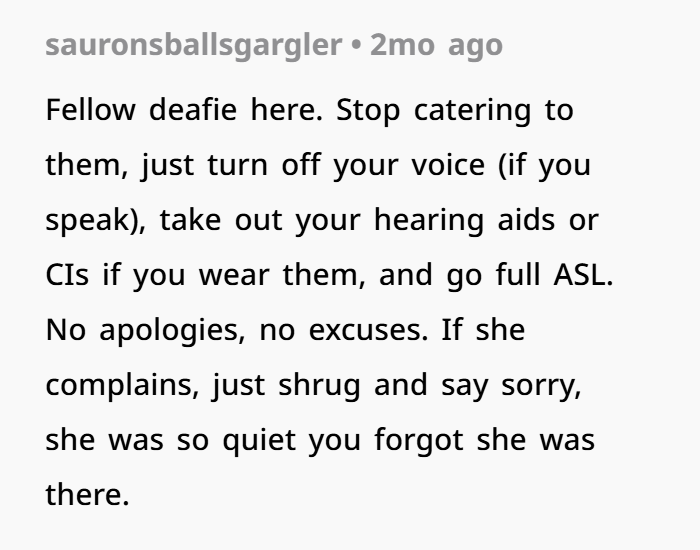

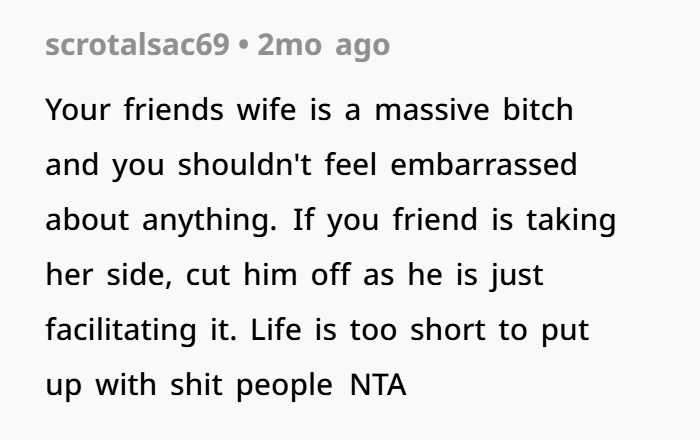

Commenters seem to side with the original poster