When Polyamory Left Me Feeling Invisible: Growing Up in My Parents’ Open Doors

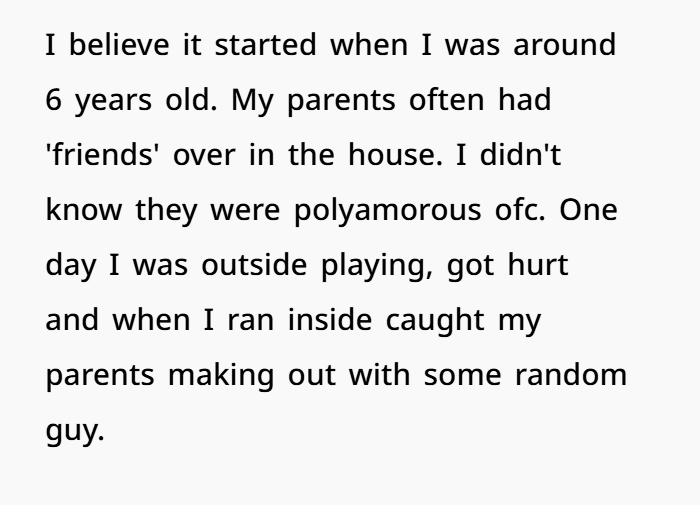

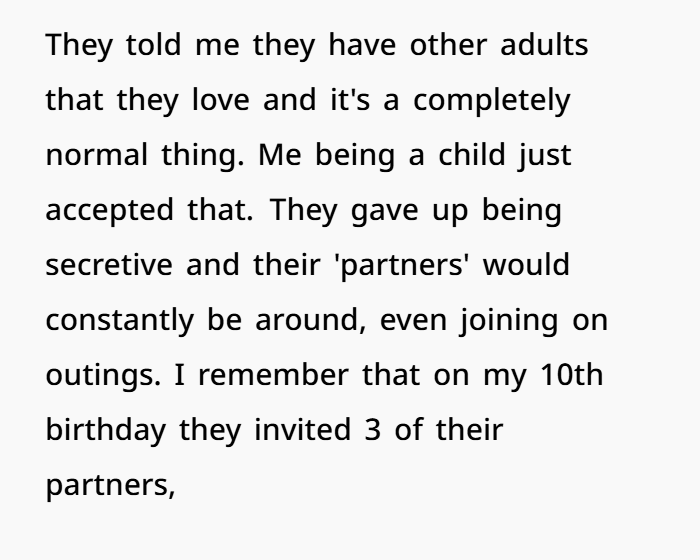

You grew up thinking nothing was wrong: your parents had “friends over” and sometimes more adults around you than you knew. As a kid, you assumed it was normal. But looking back, you realize what felt normal actually felt chaotic — birthdays, school‑nights, everyday life, all shared with multiple strangers. Even though your parents cared for you, you felt like you were competing for their attention with a revolving door of “partners.”

Now, after years in therapy and a visit from your parents asking you to vouch for polyamory in a documentary, everything came crashing down. You finally confronted them — you told them the truth: that their polyamory “fucked up” your childhood. You yelled, hurt them, made your mother cry, and now feel shame and regret for breaking silence for the first time. Deep down, though, you needed to say it.

Polyamory, a practice of having multiple partners, isn’t as uncommon as you might think

Here, the parents of today’s OP were polyamorous

Growing up in a polyamorous family isn’t a one‑size‑fits‑all experience. Some kids thrive, some feel fine, and others — like you — feel lost. Research shows both sides.

✅ The “Poly Families Can Work” Narrative

There’s a body of research by sociologists and psychologists that argues polyamorous families aren’t doomed to hurt kids. According to Elisabeth A. Sheff — who has done a 25‑year longitudinal study of poly families — many kids raised in consensual non‑monogamous (CNM) households turn out just as emotionally healthy as kids from traditional families. community.lawschool.cornell.edu+2Psychology Today+2

A more recent study published in 2024 found children growing up in polyamorous homes often view their parents’ partners as supportive adults — people they could “have fun with,” rely on for emotional support, and count on materially. INRS+2PsyPost – Psychology News+2

Many poly parents say having multiple adults around can actually benefit kids: more caregivers, more time, more stability — especially if the adults communicate well, respect boundaries, and treat the children’s needs as a priority. Psychology Today+2Greater Good+2 Think more hands in raising the child, less pressure on a single parent, more shared responsibility, sometimes more financial and emotional resources. Psychology Today+2Dr. Elisabeth “Eli” Sheff+2

Some children from poly households report advantages like open-mindedness about relationships, stronger social bonds, and comfort with complex emotional dynamics. Medium+2Psychology Today+2

So yes — there are families where polyamory doesn’t “mess up” childhood. It’s very possible that when adults are thoughtful, stable, emotionally mature, and communicative, poly‑parenting becomes a functioning — maybe even enriching — alternative to traditional parenting.

⚠️ But It Doesn’t Always Work — And Few Studies Capture the Pain

Here’s the catch: most scientific studies of poly households are skewed toward families that are “doing well.” Meaning: researchers mostly study polyamorous families that volunteered — families where polyamory “worked out” and kids seemed fine. Psychology Today+2community.lawschool.cornell.edu+2

That leaves a huge blind spot: children from poly families where the adults were messy, unstable, emotionally unavailable, or dismissive of kid‑focused boundaries — the kind of households where what you described happened. Because these families are underrepresented in research, the “positive outcomes only” narrative can feel misleading for people with experiences like yours.

Also, even in “positive” studies, many children said having multiple “parental” figures was complicated. Some kids struggled to find the right words to describe their family structure. They borrowed language from step‑families (like “step‑dad,” “step‑mom”), even when it didn’t quite fit. PsyPost – Psychology News+2ResearchGate+2

For some teenagers, those extra adults ended up being more for their parents’ happiness than for the kids’ — they didn’t build deep emotional bonds. PsyPost – Psychology News+1

Importantly: a caring multi‑adult setting only helps if the adults are committed to the child’s emotional needs. If attention is split, or if adults prioritize their romantic relationships over family time — the risk of neglect or emotional detachment rises.

🎯 Why Your Experience — and Others Like It — Doesn’t Show Up in Studies

- Voluntary participation bias: Families that are functional and stable are more likely to volunteer for longterm studies. Families in turmoil — or kids who feel hurt or resentful — usually don’t.

- Small sample sizes: For example, a 2024 study had only 18 children. PMC+2INRS+2 That’s too small to capture the wide variation of real lives — pain, neglect, competition for emotional attention, feelings of invisibility.

- Comfort with disclosure: Children may underreport negative feelings because of loyalty, shame, or fear of judgment. Some may not even have language to express what’s wrong in a non‑traditional family setup. PsyPost – Psychology News+1

- Imperfect comparison baseline: Many poly families come from liberal, socially open or financially stable backgrounds — factors that already influence children’s well‑being. So positive outcomes might owe as much to stability and resources as to polyamory itself.

Given these gaps, it’s not surprising that your painful childhood doesn’t show up in the data — but that doesn’t mean your experience is invalid.

🧠 What Experts (and Critics) Say About the Risks

Not everyone agrees polyamory is safe for kids. Some family therapists argue that polyamory can be emotionally risky — especially when kids are exposed to frequent partner turnover, fluid boundaries, and unclear parental roles. Dr. Karen Ruskin+2Public Discourse+2

In a critical analysis of poly parenting, authors argue that polyamory tends to be practiced for the adults’ emotional/sexual needs — not for children’s stability. In those cases, kids may become collateral damage. Dr. Karen Ruskin+1

When multiple adult relationships are prioritized over child‑centered parenting — when adults “live for themselves” rather than build a secure, stable world for the child — psychological consequences may include insecurity, attachment issues, feelings of rejection, and difficulty forming stable relationships in adulthood. While hard long‑term data is limited, therapists who have worked with such kids describe patterns of emotional detachment, abandonment issues, and difficulty trusting. Dr. Karen Ruskin+1

Courtrooms and legal systems are also grappling with polyamorous families because traditional custody laws don’t always recognize multi‑adult parenting. community.lawschool.cornell.edu+1 That legal ambiguity can leave children especially vulnerable if relationships break down.

🧭 So Where Does That Leave People Like You?

Your story doesn’t fit the “poly worked great for us” mold. And that’s okay. The truth is: polyamory doesn’t come with a guarantee — it’s not inherently bad, but it relies heavily on how adults treat their kids.

From what you wrote: you didn’t feel like you had a stable “home base.” Your parents’ attention was spread thin among multiple adults. Birthdays and family events weren’t about you, but about socializing. You ended up feeling like a background character in their adult lives.

That sense of invisibility — needing to compete for love and attention — can leave deep scars. Therapy often reveals pain and confusion not just about childhood, but about self‑worth, trust, boundaries, and how one expects relationships to work.

Even if some individuals from poly families turn out fine, it doesn’t erase the kids who felt lost. And that’s why your decision to speak up — even if it triggered guilt, hurt, and tears — matters.

🧰 What Research and Experts Suggest for Poly Families If They Want to Do It Right

- Prioritize children’s emotional needs over adult romance. If you choose to have a child, parenting should come first. Adults must check: “Is this lifestyle helping or hurting my child’s sense of security?”

- Use clear communication and age‑appropriate honesty. Kids should know what’s going on — not feel like secrets or strangers are normal everyday. Experts emphasize honesty, transparency, and respecting kids’ questions. Psychology Today+2Greater Good+2

- Establish stable routine and clear roles. Multiple adults around a child only helps if there’s predictability — consistent caregivers, stable schedules, defined boundaries.

- Consider long‑term well‑being, not short‑term adult fulfillment. Polyamory is often adult‑driven. But parenting needs must remain separate from adults’ sexual/romantic desires. When adults blur those lines, kids suffer.

- Provide space for children to speak out and have feelings. Just because research shows many children adapt doesn’t mean all will. Kids should have safe space to voice discomfort, jealousy, or fear — and be given respect.

📝 Why Your Feelings Are Valid — Even If Research Doesn’t Capture It

Research with small samples, volunteer bias, and “successful” poly families rarely shows stories like yours — full of confusion, competition, and emotional neglect. But that doesn’t make your pain any less real.

Studies don’t cause your childhood trauma. Real life does. And therapy isn’t about aligning with research — it’s about healing your story.

Your rage, your feeling of invisibility, your emotional distance from your parents — it’s real. You didn’t ask for a textbook definition of “normal.” You asked for love, security, stability. And in your experience, polyamory didn’t deliver that.

So when you told them “this messed me up,” you were speaking your truth. Research doesn’t erase that truth — it only shows why what happened to you might be overlooked, misunderstood, or underrepresented.

If anything, your story underscores a simple but powerful reality: parenting isn’t just about loving adults — it’s about putting the child’s needs first. When love becomes a revolving door, children sometimes get left out.